Leaders today are faced with challenges that have not been witnessed before, and these challenges will only escalate in the next 10–20 years.

Making the leap from manager to leader has always been challenging. Iain Hopkins explores what the leaders of tomorrow will be up against, and how you can identify and develop them.

Leaders today are faced with challenges that have not been witnessed before, and these challenges will only escalate in the next 10–20 years.

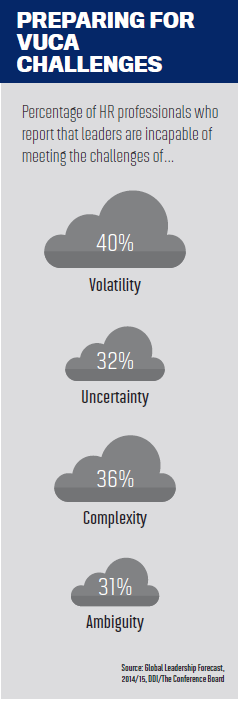

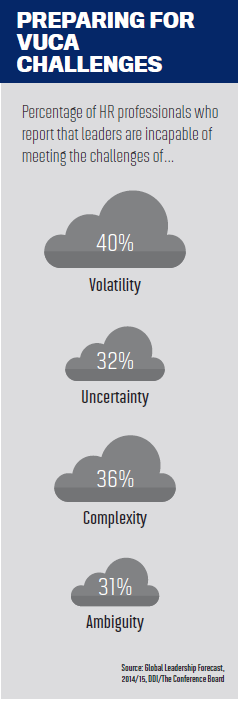

DDI groups these challenges into four key categories: VUCA.

• Volatility – anticipating and reacting to the nature and speed of change

• Uncertainty – acting decisively without 100% clear direction and certainty

• Complexity – navigating through complexity, chaos, and confusion

• Ambiguity – maintaining effectiveness despite constant surprises and a lack of predictability

Less than two-thirds of leaders around the globe said they were either ‘highly confident’ or ‘very confident’ in their ability to meet the four VUCA challenges. The result for Australian leaders was in line with their global counterparts.

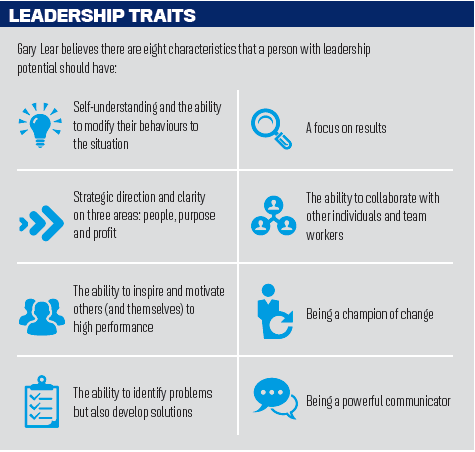

To succeed, leaders of today and tomorrow will need a diverse mix of soft skills and technical business skills. In Development Beyond Learning’s latest book, The Leader’s Edge, these skills are summarised under the acronym SMART:

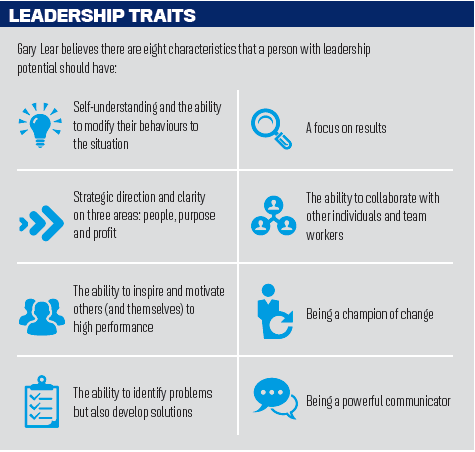

Situational understanding. A leader begins by assessing where their company is as an organisation and then where they need to move to in three main areas: people, purpose and performance. “It’s understanding the current situation and where you personally fit into that, and how the rest of your team sits in relation to those elements,” explains Gary Lear, chairman and co-founder, Development Beyond Learning.

Motivating. “With all the challenges that are placed on a leader’s head, one of the most important factors is the ability to motivate themselves and then motivating others to create a high performing team,” Lear explains.

Advancing goals. “Taking a business forward is not just about behavioural leadership but how you set a great strategy. Setting a great strategy and vision is important for the organisation, and advancing goals is based on that strategy and vision,” says Lear.

Reviewing actions. “The leader must be able to place things in context in their org and within their global focus. They must then be able to move people and their people structures forward to adapt to any upcoming changes,” says Lear.

Tracking progress. “This means consistently reviewing your own leadership and your organisation’s progress,” says Lear. “One of the biggest problems we get into is almost like a treadmill of doing the same thing every day and expecting a different result. Leaders need to start looking at tracking progress so they can bring about change quickly within their organisation.”

Are we prepared?

If these external challenges are daunting, it’s nothing compared to what organisations are up against internally. Over the last five years, Lear has seen a contraction of focus on leadership development within organisations. This, he notes, is a ripple effect of the GFC, which focused most CEOs on the bottom line rather than on people development.

“The challenge we’ve got right now is getting the CEO’s eyes off the bottom line and onto their people. One of the problems is they don’t realise

that their people are their organisation. They are creating a leadership capability gap which is going to be hard to fill,” he says.

Part of the problem is a failure to map out explicit career opportunities and paths to upcoming leaders. In the past, individuals could enter an organisation and conformably spend the next 20 years working their way through a relatively static and defined career path. In today’s VUCA world, this is tough.

Organisations are constantly changing and reshaping their structures. This can make it challenging to map out well-defined career paths over a long period of time.

However, research shows that career paths remain important and contribute to employee engagement and retention. So, what can organisations and leaders do to manage this need in a very different business context?

Dan Musson, chief executive of the Australian Institute of Management (AIM), suggests some of this comes down to changes in organisational hierarchies. Where once there were deep hierarchical structures, with a career path seemingly for each individual, this no longer applies in 2015. At the same time, career development has been handed over to the individuals themselves to manage.

“Managers are out of practice in looking for and developing the capability within their company. They’re focused on their job, and developing future leaders is kind of a secondary thing, or an HR thing,” he says.

This concept of the ‘free agent’ has taken flight among younger workers. Employees are free to move between companies and industries, and they have capabilities that extend across multiple areas. Yet this does not mean employers can take a hands-off stance. Employees still need clarity or direction, even in a flat organisation.

“You can’t just say, ‘Let us know what development you want to do and we’ll let you know if we’ll fund it’,” Musson says. “That’s too ad hoc. People get lost in that. They will understand that lateral movements are just as valuable as moves up the hierarchy because there are fewer opportunities upwards – but they need a very deliberate direction.”

He suggests that managers must take an active role, either as mentor or coach. “That has to be part of the leader’s job now. How much am I spending developing capability as part of my day?” he says.

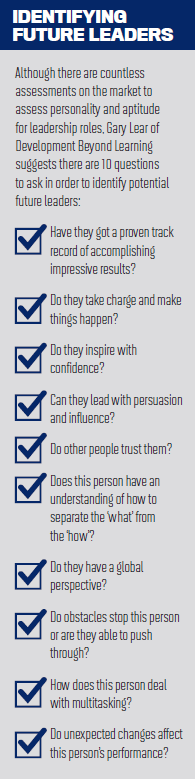

Mark Busine, managing director of DDI, suggests: “One of the first things leaders can do is to ensure that individuals (right across the leadership pipeline) have development plans in place.

“In the absence of clearly defined career paths, leaders need to work with their team members to ensure they are receiving the opportunities that facilitate growth and development. This includes looking out for the roles, experiences and opportunities that will facilitate growth and support engagement.”

Sadly, only 36% of a sample of more than 13,000 leaders reported having an up-todate development plan.

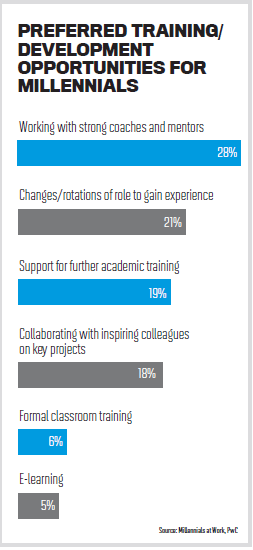

Leadership development for millennials

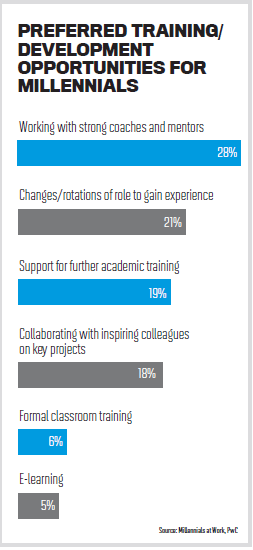

By 2025, millennials (those born 1981–1997) will represent 75% of the workforce. DDI’s Global Leadership Forecast research found the engagement level of this group can be raised by providing them with a greater understanding of their career path as leaders. The challenge is how you do this in a business context that is frequently changing.

“Providing Millennials an awareness of a range of possible paths that may be ahead of them – not a single route from point A to point B as on a map – is the key, and managers need to know how to tap into these motivators and opportunities,” suggests Busine. He adds that this can be achieved by having career conversations: what do millennials want and what do they expect?

Importantly, millennials want leadership modelling right now.

“They want to have leadership that they can see and use as a model for the future,” says Lear. “They’re asking for leadership.” The most successful organisations, he adds, already have managers who model leadership for their millennials. These managers are also clear on the purpose of an organisation (‘why are we doing this?’), which is a critical element for millennial engagement.

element for millennial engagement.

“We’re working closely with the managers of Millennials, to engage them in developing their teams,” says Lear, who adds that ‘engagement dynamics’ is one way to build this bond. Engagement dynamics brings together both parties in scenario-based learning to develop the manager as well as the young professional.

Development Beyond Learning also offers ‘action learning periods’. “Our programs are not just two days face-to-face and then out of the room. We carry that through a period of six months, which brings about a change in behaviour. You learn a behavior over a long period of time; you won’t bring about change in that behavior in a period of two days,” Lear says.

And of course, for this always-connected generation, access to learning 24/7 is critical. Gamified apps and integrating social learning into development programs – via virtual learning platforms – are also important.

Musson suggests that not only have millennials been exposed to learning and generally want more of it, but there has been growth in what he calls just-in-time learning. Facilitated by technology, just-in-time learning will occur when an individual wants to undertake just a small chunk of learning just in time for a new career step – whether that’s from manager to leader – or just in time for a change of industry or job.

“We’re no longer seeing education and learning as something where you tick off three courses and as soon as that’s done you’ve got the foundation and you can move on. Today it’s more fluid. It’s up to us as a supplier to say, ‘OK, which short courses are people going to want? How will they get it delivered?’”

For example, AIM has just rolled out its MBA program in an online format because Musson says that even with formal education people are looking for the flexibility that technology provides.

“The challenge for us is not just how we take a face-to-face environment and put it online, but it’s about how do we compete with the latest movie or latest game,” Musson says. “This generation is referred to as the digital “The challenge for us is not just how we take a face-to-face environment and put it online, but it’s about how do we compete with the latest movie or latest game,” Musson says. “This generation is referred to as the digital

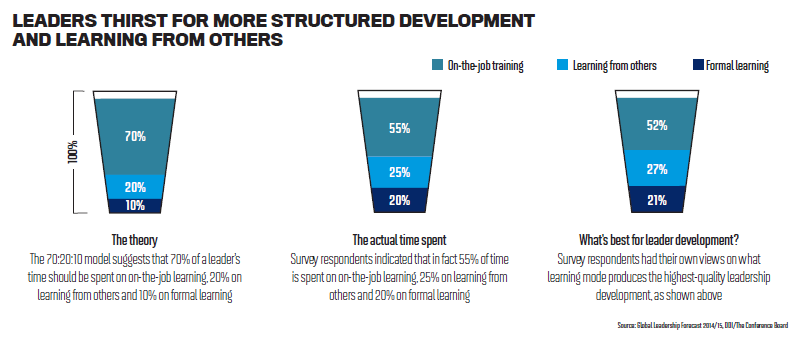

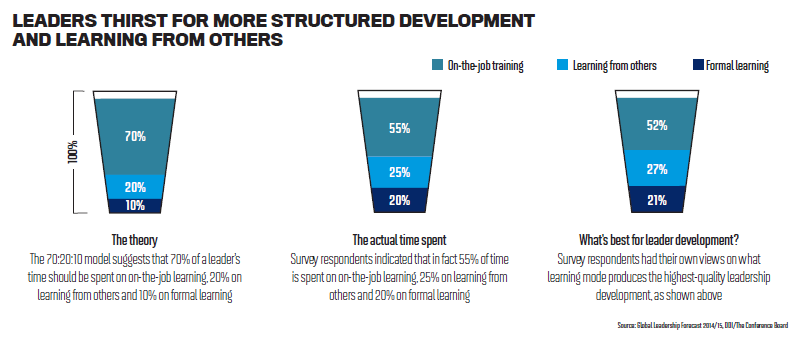

One thing is clear: leadership development is not solved by a single solution or one-sizefits-all approach. The concept of the 70:20:10 development model (see box below) suggests that a good development experience will involve a variety of different learning and development methods and approaches – yet Busine suggests that too much emphasis has been placed on the ratio, and this was never the intention of the original developers of the concept.

“Most people can readily identify people who have been great coaches or mentors throughout their careers. Unfortunately they can’t always identify multiple people, and more often than not their examples don’t include their own managers from across their career,” he says.

Musson agrees, and says it’s only through the application of theory that the student and the company will get a return on the investment of training. “I’m also a fan of the coaching component that sits in and around that model,” he says. “It embeds the learning. It’s not now HR’s job or it’s not AIM’s job to deliver it. It’s embedded in the company.”

A first step is to turn leaders and managers into better coaches and ensure they have the skills to effectively coach their team members (formally and informally); secondly, (and driven by a particular need and/or development goal), to provide individuals with access to other coaches and mentors both inside and outside the organisation.

A first step is to turn leaders and managers into better coaches and ensure they have the skills to effectively coach their team members (formally and informally); secondly, (and driven by a particular need and/or development goal), to provide individuals with access to other coaches and mentors both inside and outside the organisation.

Echoing Lear’s view that millennials want to learn from their own managers, DDI’s Global Leadership Forecast indicates that 71% of leaders surveyed would like to spend more time learning from others. This compares with just 26% who indicated they would like to spend more time learning on the job. Interestingly, 76% indicated they would like to spend more time in formal learning.

“It’s amazing to watch how people develop using their own learning style, their own processes, but doing it themselves with the support of some good books, some online assessments, some videos and audios. They can choose which way they want to learn. Some people learn through watching; others learn through doing,” says Lear.

Leaders today are faced with challenges that have not been witnessed before, and these challenges will only escalate in the next 10–20 years.

DDI groups these challenges into four key categories: VUCA.

• Volatility – anticipating and reacting to the nature and speed of change

• Uncertainty – acting decisively without 100% clear direction and certainty

• Complexity – navigating through complexity, chaos, and confusion

• Ambiguity – maintaining effectiveness despite constant surprises and a lack of predictability

Less than two-thirds of leaders around the globe said they were either ‘highly confident’ or ‘very confident’ in their ability to meet the four VUCA challenges. The result for Australian leaders was in line with their global counterparts.

To succeed, leaders of today and tomorrow will need a diverse mix of soft skills and technical business skills. In Development Beyond Learning’s latest book, The Leader’s Edge, these skills are summarised under the acronym SMART:

Situational understanding. A leader begins by assessing where their company is as an organisation and then where they need to move to in three main areas: people, purpose and performance. “It’s understanding the current situation and where you personally fit into that, and how the rest of your team sits in relation to those elements,” explains Gary Lear, chairman and co-founder, Development Beyond Learning.

Motivating. “With all the challenges that are placed on a leader’s head, one of the most important factors is the ability to motivate themselves and then motivating others to create a high performing team,” Lear explains.

Advancing goals. “Taking a business forward is not just about behavioural leadership but how you set a great strategy. Setting a great strategy and vision is important for the organisation, and advancing goals is based on that strategy and vision,” says Lear.

Reviewing actions. “The leader must be able to place things in context in their org and within their global focus. They must then be able to move people and their people structures forward to adapt to any upcoming changes,” says Lear.

Tracking progress. “This means consistently reviewing your own leadership and your organisation’s progress,” says Lear. “One of the biggest problems we get into is almost like a treadmill of doing the same thing every day and expecting a different result. Leaders need to start looking at tracking progress so they can bring about change quickly within their organisation.”

Are we prepared?

If these external challenges are daunting, it’s nothing compared to what organisations are up against internally. Over the last five years, Lear has seen a contraction of focus on leadership development within organisations. This, he notes, is a ripple effect of the GFC, which focused most CEOs on the bottom line rather than on people development.

“The challenge we’ve got right now is getting the CEO’s eyes off the bottom line and onto their people. One of the problems is they don’t realise

that their people are their organisation. They are creating a leadership capability gap which is going to be hard to fill,” he says.

Part of the problem is a failure to map out explicit career opportunities and paths to upcoming leaders. In the past, individuals could enter an organisation and conformably spend the next 20 years working their way through a relatively static and defined career path. In today’s VUCA world, this is tough.

Organisations are constantly changing and reshaping their structures. This can make it challenging to map out well-defined career paths over a long period of time.

However, research shows that career paths remain important and contribute to employee engagement and retention. So, what can organisations and leaders do to manage this need in a very different business context?

Dan Musson, chief executive of the Australian Institute of Management (AIM), suggests some of this comes down to changes in organisational hierarchies. Where once there were deep hierarchical structures, with a career path seemingly for each individual, this no longer applies in 2015. At the same time, career development has been handed over to the individuals themselves to manage.

“Managers are out of practice in looking for and developing the capability within their company. They’re focused on their job, and developing future leaders is kind of a secondary thing, or an HR thing,” he says.

This concept of the ‘free agent’ has taken flight among younger workers. Employees are free to move between companies and industries, and they have capabilities that extend across multiple areas. Yet this does not mean employers can take a hands-off stance. Employees still need clarity or direction, even in a flat organisation.

“You can’t just say, ‘Let us know what development you want to do and we’ll let you know if we’ll fund it’,” Musson says. “That’s too ad hoc. People get lost in that. They will understand that lateral movements are just as valuable as moves up the hierarchy because there are fewer opportunities upwards – but they need a very deliberate direction.”

He suggests that managers must take an active role, either as mentor or coach. “That has to be part of the leader’s job now. How much am I spending developing capability as part of my day?” he says.

Mark Busine, managing director of DDI, suggests: “One of the first things leaders can do is to ensure that individuals (right across the leadership pipeline) have development plans in place.

“In the absence of clearly defined career paths, leaders need to work with their team members to ensure they are receiving the opportunities that facilitate growth and development. This includes looking out for the roles, experiences and opportunities that will facilitate growth and support engagement.”

Sadly, only 36% of a sample of more than 13,000 leaders reported having an up-todate development plan.

Leadership development for millennials

By 2025, millennials (those born 1981–1997) will represent 75% of the workforce. DDI’s Global Leadership Forecast research found the engagement level of this group can be raised by providing them with a greater understanding of their career path as leaders. The challenge is how you do this in a business context that is frequently changing.

“Providing Millennials an awareness of a range of possible paths that may be ahead of them – not a single route from point A to point B as on a map – is the key, and managers need to know how to tap into these motivators and opportunities,” suggests Busine. He adds that this can be achieved by having career conversations: what do millennials want and what do they expect?

Importantly, millennials want leadership modelling right now.

“They want to have leadership that they can see and use as a model for the future,” says Lear. “They’re asking for leadership.” The most successful organisations, he adds, already have managers who model leadership for their millennials. These managers are also clear on the purpose of an organisation (‘why are we doing this?’), which is a critical

element for millennial engagement.

element for millennial engagement.“We’re working closely with the managers of Millennials, to engage them in developing their teams,” says Lear, who adds that ‘engagement dynamics’ is one way to build this bond. Engagement dynamics brings together both parties in scenario-based learning to develop the manager as well as the young professional.

Development Beyond Learning also offers ‘action learning periods’. “Our programs are not just two days face-to-face and then out of the room. We carry that through a period of six months, which brings about a change in behaviour. You learn a behavior over a long period of time; you won’t bring about change in that behavior in a period of two days,” Lear says.

And of course, for this always-connected generation, access to learning 24/7 is critical. Gamified apps and integrating social learning into development programs – via virtual learning platforms – are also important.

Musson suggests that not only have millennials been exposed to learning and generally want more of it, but there has been growth in what he calls just-in-time learning. Facilitated by technology, just-in-time learning will occur when an individual wants to undertake just a small chunk of learning just in time for a new career step – whether that’s from manager to leader – or just in time for a change of industry or job.

“We’re no longer seeing education and learning as something where you tick off three courses and as soon as that’s done you’ve got the foundation and you can move on. Today it’s more fluid. It’s up to us as a supplier to say, ‘OK, which short courses are people going to want? How will they get it delivered?’”

For example, AIM has just rolled out its MBA program in an online format because Musson says that even with formal education people are looking for the flexibility that technology provides.

“The challenge for us is not just how we take a face-to-face environment and put it online, but it’s about how do we compete with the latest movie or latest game,” Musson says. “This generation is referred to as the digital “The challenge for us is not just how we take a face-to-face environment and put it online, but it’s about how do we compete with the latest movie or latest game,” Musson says. “This generation is referred to as the digital

One thing is clear: leadership development is not solved by a single solution or one-sizefits-all approach. The concept of the 70:20:10 development model (see box below) suggests that a good development experience will involve a variety of different learning and development methods and approaches – yet Busine suggests that too much emphasis has been placed on the ratio, and this was never the intention of the original developers of the concept.

“Most people can readily identify people who have been great coaches or mentors throughout their careers. Unfortunately they can’t always identify multiple people, and more often than not their examples don’t include their own managers from across their career,” he says.

Musson agrees, and says it’s only through the application of theory that the student and the company will get a return on the investment of training. “I’m also a fan of the coaching component that sits in and around that model,” he says. “It embeds the learning. It’s not now HR’s job or it’s not AIM’s job to deliver it. It’s embedded in the company.”

A first step is to turn leaders and managers into better coaches and ensure they have the skills to effectively coach their team members (formally and informally); secondly, (and driven by a particular need and/or development goal), to provide individuals with access to other coaches and mentors both inside and outside the organisation.

A first step is to turn leaders and managers into better coaches and ensure they have the skills to effectively coach their team members (formally and informally); secondly, (and driven by a particular need and/or development goal), to provide individuals with access to other coaches and mentors both inside and outside the organisation.Echoing Lear’s view that millennials want to learn from their own managers, DDI’s Global Leadership Forecast indicates that 71% of leaders surveyed would like to spend more time learning from others. This compares with just 26% who indicated they would like to spend more time learning on the job. Interestingly, 76% indicated they would like to spend more time in formal learning.

“It’s amazing to watch how people develop using their own learning style, their own processes, but doing it themselves with the support of some good books, some online assessments, some videos and audios. They can choose which way they want to learn. Some people learn through watching; others learn through doing,” says Lear.