Mortgage arrears rise, banks well prepared

Released this week, the New Zealand Financial Stability Report provides half-yearly insights into the health of the country's financial system.

Here are four key takeaways from the May 2024 report, with commentary from Chris McDonald, manager of system monitoring and analysis at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (Te Pūtea Matua).

- Resilience in a high-interest environment

After enjoying a decade of low rates, Kiwis were hit with a rapid rate rising cycle in the past couple of years, indebting households and businesses alike.

Largely spurred on by global forces, RBNZ said higher interest rate costs are a “key focus” given its implications to financial stability.

Each time the lever to raise rates was pulled by the central bank, the ripple effect on borrowers was far reaching. However, to date, the impacts of higher interest rates on the financial system have been “more benign than generally expected”.

Still, a further increase in defaults as borrowers fall behind on their debt repayments would result in losses to banks and, on a large enough scale, could lead to financial instability, according to the central bank which is set to decide the cash rate on May 21.

But for now, the New Zealand financial system has largely held up.

“Globally, inflation is generally declining, and most people expect interest rates in major economies will come down over the next year, so long as inflation continues to fall,” said McDonald.

“So far, the global financial system has been resilient to high interest rates, particularly because job losses have not been widespread.”

Concerningly, some economists have suggested that rates could still track higher based on recent global and local data.

- Mortgage repricing is now well advanced

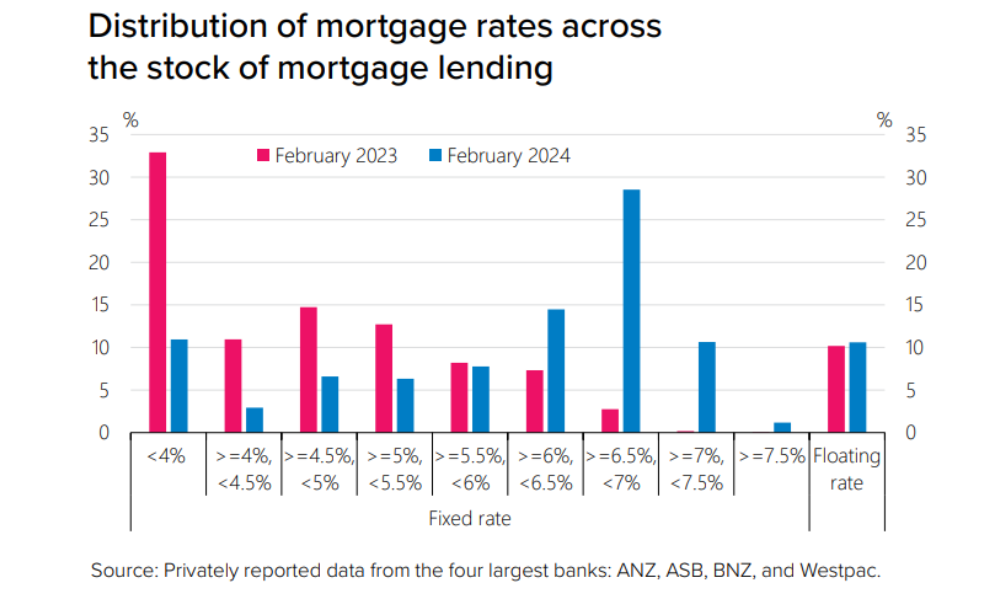

Most borrowers have moved off the low fixed mortgage rates that were locked in two to three years ago onto much higher rates, with only around 10% of mortgage lending remaining on fixed rates below 4%.

As a result, the average rate across the stock of lending is about 85% of the way to its projected peak.

This rate has increased to 6.0% from a low of 2.8% in 2021.

The report found it will likely continue to increase to around 6.5% at around the end of this year based on the forward path of interest rates implied by market pricing.

“Most households with mortgages in New Zealand have now rolled on to higher interest rates,” said McDonald.

“Unfortunately, some people have fallen behind on their mortgage repayments, but that number is low compared to previous periods of stress, such as the global financial crisis.”

“To make ends meet, households have had to pull back on their discretionary spending and reduce how quickly they repay their mortgage.”

- Mortgage arrears continue to rise from recent lows

While most have adapted, a small proportion of borrowers have fallen in arrears.

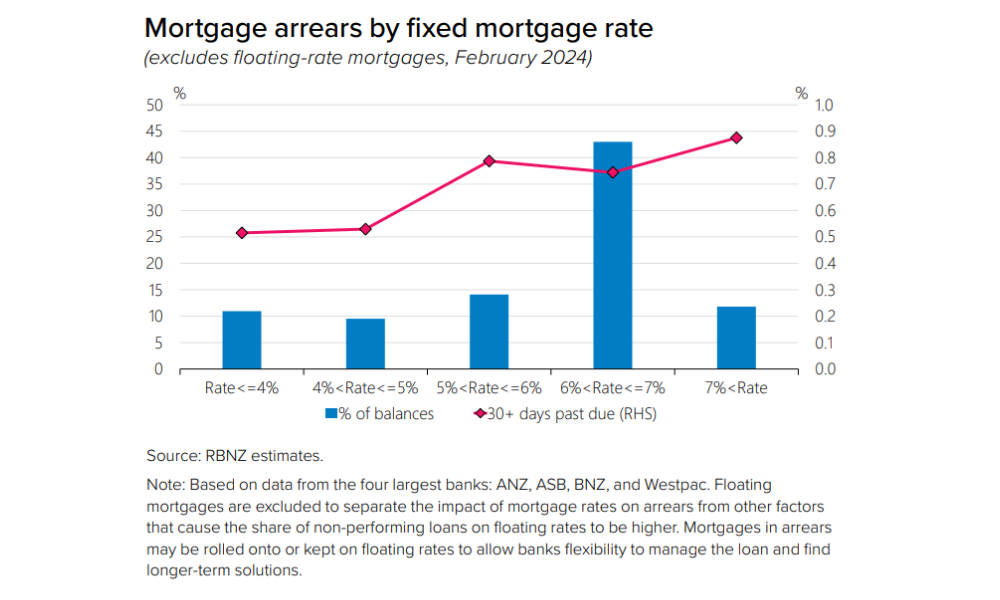

The report said difficulty in keeping up with payments has likely been made worse by cost-of-living pressures and other unforeseen events like job losses. As a result, an increasing share of mortgage lending has been categorised as non-performing (defined as those 90 or more days in arrears or impaired).

This share has increased from extremely low 0.2% in 2022 to around 0.5% currently.

“We also monitor the share of lending that is 30 days or more past due as a leading indicator of future non-performing loans,” the report said. “The share has also gradually increased to slightly above the 2020 peak.”

A similar trend can also be seen in hardship cases, where borrowers have suffered unforeseen circumstances that have needed them to change their debt repayments to be able to pay their mortgage.

Data from the four largest banks show that the non-performing share is higher for lending already on higher mortgage rates, highlighting the link between debt servicing costs and borrower cash flow pressures.

In terms of who is most affected, the general trend is bigger loans, bigger strains. Borrowers with high debt-to-income ratios (especially aged 30-50) are particularly feeling the pinch.

2021's low interest rates fuelled a surge in high-risk lending (DTI > 6) as affordability assessments used lower rates of around 6% for new lending.

“House prices have been relatively stable over the past year, as high interest rates continue to limit what buyers can afford to borrow,” McDonald said.

“Looking ahead, our proposed debt-to-income restrictions will help prevent a rise in risky mortgage lending, particularly during periods of low interest rates.”

- Banks well positioned

Although more borrowers are switching to higher mortgage rates, leading to a slight increase in arrears, the Reserve Bank reassures us that most of this transition has already happened.

They expect non-performing loans to only reach 0.7% by year-end.

However, this came with a caveat: “the impact of higher debt servicing costs is also often only fully realised after some time, as a strained borrower exhausts savings and other buffers”.

Either way, McDonald said banks are “well placed” to handle any economic downturns. Borrowers still have capacity to handle high debt servicing costs, either through reducing principal repayments or drawing on savings buffers.

As an example, an option for borrowers in financial stress is to pay only the interest costs and stop principal repayments. But over the past year, the share of interest-only mortgages has remained flat at historically low levels.

Despite this, a small portion of borrowers will have few options available and are at risk of default.

“Robust labour market conditions and strong nominal wage growth have supported borrowers over recent years. In general, if a mortgage holder still has a job, they can find ways to manage their repayments,” the report said.

“However, with most economic forecasters expecting the unemployment rate to increase over the next year, a softer labour market is likely to lead to an increase in arrears.”

Meanwhile, non-bank lenders (building societies, credit unions, specialist lenders, etc) are a mixed bag. While the sector is small compared to banks ($2.2 billion in lending), it serves many customers.

New lending has slowed across the board (especially for building societies and credit unions) due to higher interest rates, lower credit demand, and economic uncertainty. Despite some consolidation efforts, smaller non-bank lenders may struggle in this environment.

But overall, McDonald said “the New Zealand financial system remains strong as it continues to adjust to the higher interest rate environment.”

To view the Financial Stability Report, click here.